"Though plenty was left after death, he forgot

to hold his hand back;

Only at the end of the road does one think of

turning on to the right track."

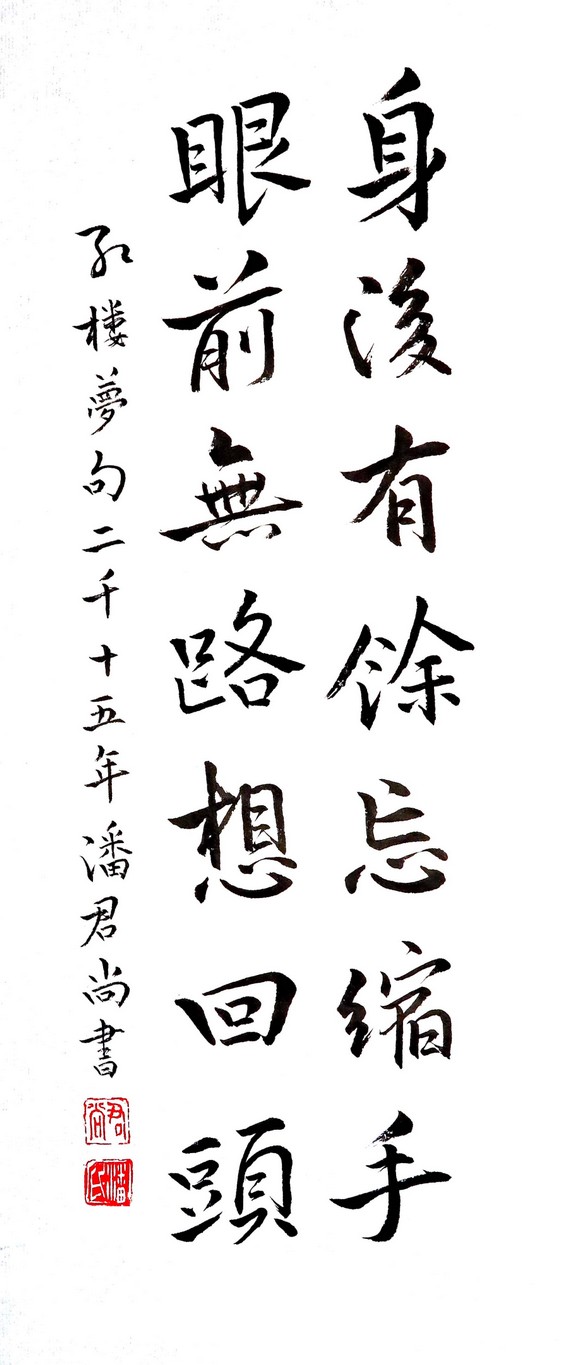

身後有餘忘縮手,眼前無路想回頭。

65 X 35cm

"Though plenty was left after death, he forgot to hold his hand back; Only at the end of the road does one think of turning on to the right track."

-- A couplet verse from Dream of the Red Chamber

(身後有餘忘縮手,眼前無路想回頭。-- 紅樓夢句)

40 X 17cm in Semi-cursive Script (行書)

Historical information

Dream of the Red Chamber (紅樓夢), also known as The Story of the Stone (石頭記), is widely recognized as one of the best Chinese literary works in history (1,2). Written by Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹) of the 18th century, tthe novel narrates the downfall of the illustrious Jia (賈) family with Jia Baoyu (賈寶玉), the male heir of the family, as the main character. Elegant words, beautiful poems, and thought-provoking phrases traverse the delicate and detailed plot that is profoundly philosophical. The entire work is so highly regarded by many that it spawned "Redology"(紅學), a specialized academic stream that examines the Dream of the Red Chamber (3,4). It is, hence, not an overstatement that the Dream of the Red Chamber can match, if not exceed, any work written by Shakespeare.

This particular couple verse appears in Chapter 2 of the novel. The English translation presented here is from Yang Xianyi's (楊憲益) English interpretation of the Dream of the Red Chamber (5) published between 1978-1980. Sinologist David Hawkes had also translated the Dream of the Red Chamber around that time, but Yang's translation of this verse is more accurate (see here). Interestingly, it has been recently discovered that another venerable writer and translator, Lin Yutang (林語堂), had also attempted to translate Dream of the Red Chamber into English (6).

Text Translation

"Though plenty was left after death, he forgot to hold his hand back;

Only at the end of the road does one think of turning on to the right track."

Personal Comments

Any worldly possession can be washed away in an instant, and so this verse serves as an excellent admonition for all. Indeed, those who pursue worldly possessions as their ultimate life goals are idiots (蠢物, see chapter 1 of the novel).

One couplet verse in the novel's opening chapter deserves some discussusion:

"假作真時真亦假,無為有處有還無。"“When false is taken for true, true becomes false; If non-being turns into being, being becomes non-being.”(Translated by Yang Xianyi and Gladys Yang).

Yang's translation here is more accurate than the more popular David Hawkes' translation:

"Truth becomes fiction when the fiction's true; Real becomes not-real where the unreal's real."(Translated by David Hawkes)

The Chinese words "假" and "無" are critical to correctly understand this couple verse. "假" carries not only the meaning of "false" and "fiction" but also carries the meaning of "illusion" and "virtual (幻)". "無" carries not only the meaning of "non-real" and "non-being" but also carries the meaning of "non-concrete existence (虛)", similar to the Buddhist concept of Impermanence (無常). Accordingly, the verse suggests that all things we experience are non-concrete illusions.

As an aside, author Cao Xueqin and translator Yang Xianyi both suffered immense tragedies in their lifetimes: Cao Xueqin lived in extreme poverty throughout his entire life due to Emperor Yongzheng (雍正帝) confiscation of his illustrious family's fortunes (7,8); Yang Xianyi and his wife Gladys Yang were labelled as "class enemies" in 1964 and "spent seven years apart in different jails" during the Communist Chinese Cultural Revolution (9).

Alas, tragedies await for those who are talented.

Jump to: Poetry and Others