Footnotes on the English Translation of “A Narrative on Calligraphy” Part VIII

(163,164). 規模所設 – “規模” here means “格局(setup/layout)”. In Chinese calligraphy, this refers to character structures and overall layouts (布局) such as the arrangements of black and white spaces within a character, between characters, and among rows of characters (分行布白, 計白當黑). For further discussions, please see Leung Pai Wan’s (梁披雲)《中國書法大辭典》(廣東: 廣東人民出版社,1991, p.170).

It is incorrect to interpret “規模” here as “norms” (Chang and Frankel, Two Chinese Treatises on Calligraphy, New Haven & London: Yale University Press, 1995 :11) nor “rules” (De Laurentis, The Manual of Calligraphy by Sun Guoting of the Tang, Napoli: Universita degli Studi di Napoli "L'Orientale", 2011:55) since subsequent lines focus on the discussion of character structures and overall layouts in calligraphy.

“設” means “陳列/安置 (arrangement/organization)” in this context.

(165). 信屬目前 – “目前” means “現在(at this instant)”. In this context, it should be interpreted as “at the instant of penning calligraphy”.

(183). 通會之際,人書俱老 – This particular sentence resonates with Line 103 : “體老壯之異時,百齡俄頃( by the time one experiences and comprehends the distinct differences of the artistic flavors exhibited between the older and the younger self, a lifetime has already passed in an instant)”.

(184). 仲尼云:「五十知命。七十從心。」 - This sentence refers to a passage in The Analects - Wei Zheng (《論語•為政》):

子曰:「吾十有五而志于學,三十而立,四十而不惑,五十而知天命,六十而耳順,七十而從心所欲,不踰矩。」

The Master said, "At fifteen, I had my mind bent on learning. At thirty, I stood firm. At forty, I had no doubts. At fifty, I knew the decrees of Heaven. At sixty, my ear was an obedient organ for the reception of truth. At seventy, I could follow what my heart desired, without transgressing what was right." – translated by James Legge.

(185). 故以達夷險之情 – “夷” is “平”, therefore “夷險” is “平險”, which in turns refers to “平正” and “險絕” in Lines 195 to 197.

(187). 時然後言 – This phrase is from The Analects – Xian Wen (《論語•憲問》):

夫子時然後言。

My master speaks when it is the time to speak - translated by James Legge.

(188,189). 而風規自遠– “風規” in this context is “文藝作品的風格(artistic fashion)”, “遠” refers to “高遠 (grand and noble)”. Therefore, the proper vernacular Chinese interpretation of “而風規自遠” is:

而風格自然便是高遠。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)

It is certainly not “[thus making] his style unachievable [by other calligrapher]” (De Laurentis: 56) nor “because his personality was controlled and far-reaching” (Chang and Frankel: 12).

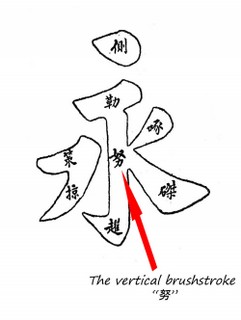

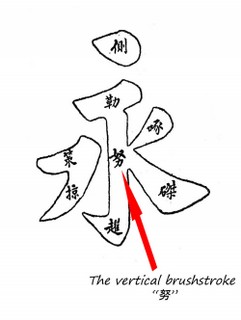

(190,191). 莫不鼓努為力 – “鼓努” here is “exerting one’s greatest might in penning the vertical brushstroke”; “努” in Chinese calligraphy refers to penning the vertical stroke as indicated in 《書苑菁華•永字八法》:

“為豎必努……,努不宜直。直則失力。”(中央研究院 搜詞尋字)

Pictorially, “努” is:

Source: 潘國鍵宗哲書法講座, http://poonkwokkin.com/Calligraphy_Video/Call_V_4.html .

As such, “力” is “筆力(strength in applying the brush)” .

“莫不鼓努為力, 標置成體” can therefore be interpreted in vernacular Chinese as:

無不奮力寫那「豎直」以為筆力,標榜自己學成了某一家的字體 。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)

Note also “標置成體” does not refer to one developing a distinguished font on their own, as suggested in many English and vernacular Chinese interpretations; the main idea of this phrase is to describe all learners (莫不) were trying to accomplish (成) to write in an established “set standard font”(字體) (eg. in a font that resembled Wang Xizhi’s). This phrase resonates with Line 177’s “莫不強名為體 (they are all compelled to classify the art into the so-called standard set fonts)”.

Accordingly, the following interpretations of “莫不鼓努為力, 標置成體” are incorrect:

-“calligraphers have strained too hard and used affectations to form a personal style.” (Chang and Frankel:12)-“everyone has tried hard [to show] vigor, establishing models and creating forms artificially.”(De Laurentis:56)

(192,193). 豈獨工用不侔 – “工用” means “力氣(effort)” as indicated in the poem 《晚燕》composed by Tang Dynasty poet Bai Juyi (白居易) :

不悟時節晚,徒施工用多。Not realizing the times were too late, all that much effort had gone to waste.(translated by KS Vincent Poon)

“侔” means “配(match/in accord)” as suggest in Zhuangzi - Inner Chapters - The Great and Most Honoured Master (《莊子•內篇•大宗師》) :

畸人者,畸於人而侔於天。He stands aloof from other men, but he is in accord with Heaven. - translated by James Legge .

Therefore, the vernacular Chinese interpretation of “豈獨工用不侔” should be:

何止所費力氣[與效果]不相配。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)

As such, “豈獨工用不侔,亦乃神情懸隔者也” should not be interpreted as “How is it then possible that only technique and application are not the same[from the past]: spirit and expressiveness also are very different!” (De Laurentis:57)

(194,195,196). 自矜者將窮性域,絕於誘進之途- “窮” here means “止絕(insulate)”, “性域” refers to “性情境界(the realm of emotions)”, “誘進” is “誘導進取(directed improvement)”. As such, the proper vernacular Chinese interpretation should be:

自滿自誇的人,將會自絕於[書法] 情性的境域,亦 斷絕了循循善誘得而上進的道路 。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)

Thus, to interpret “將窮性域” as “reach a limit” (Chang and Frankel:12) is completely incorrect.

(197,198,199,200). 自鄙者尚屈情涯, 必有可通之理– Here, “尚” means “庶幾/差不多(almost)”, 屈 is “斷絕(completely disconnected)”, and “情涯” represents “shores of emotions”. “涯” takes the meaning of “banks/shores” as suggested in The Book of Documents - Shang Shu - Count of Wei (《尚書•商書•微子》):

若涉大水,其無津涯。

its condition is like that of one crossing a stream, who can find neither ford nor bank. - translated by James Legge.

Also, “理” in this sentence should be interpreted as “道(principle)”.

Together, the entire sentence should then be interpreted in vernacular Chinese as:

自覺鄙陋不足的人,雖差不多也隔斷了情性的邊岸,卻仍必有可以通達的道理。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)

“尚屈情涯” is therefore not “inhibited” (Chang and Frankel:12) nor “have frustrated emotions” (De Laurentis:57).

(201). 蓋有學而不能 – “能” here means “善也/勝任(good at/master)”, see Kangxi Dictionary《康熙字典》.

(202). 考之即事 – “即事” means “面對眼前事物(with regards to the current matter at hand)”. Therefore, “考之即事” in this context should be interpreted in vernacular Chinese as:

探索一下眼前所討論的書法這事情 。(interpreted by Kwok Kin Poon)